Beyond the Silicon Ceiling: The Salk Institute and the Infinite Scalability of the Human Brain

When scientists at the Salk Institute mapped a tiny portion of the hippocampus using nanometer-scale 3D microscopy, they weren’t expecting to redefine the limits of computation. Yet their data — later published in eLife — showed that each synapse can encode about 4.7 bits of information, far exceeding prior assumptions about neural precision. Extrapolated across the brain’s estimated 26 trillion synapses, that yields a memory capacity of roughly a petabyte, on par with the entire global internet.

But capacity is only part of the story. The brain performs this vast computation on 20 watts of energy — less than the power draw of a dim bulb. The Salk findings, coupled with Terrence Sejnowski’s decades of work in computational neurobiology, point toward a deeper truth: the human brain is not merely efficient — it is unbounded.

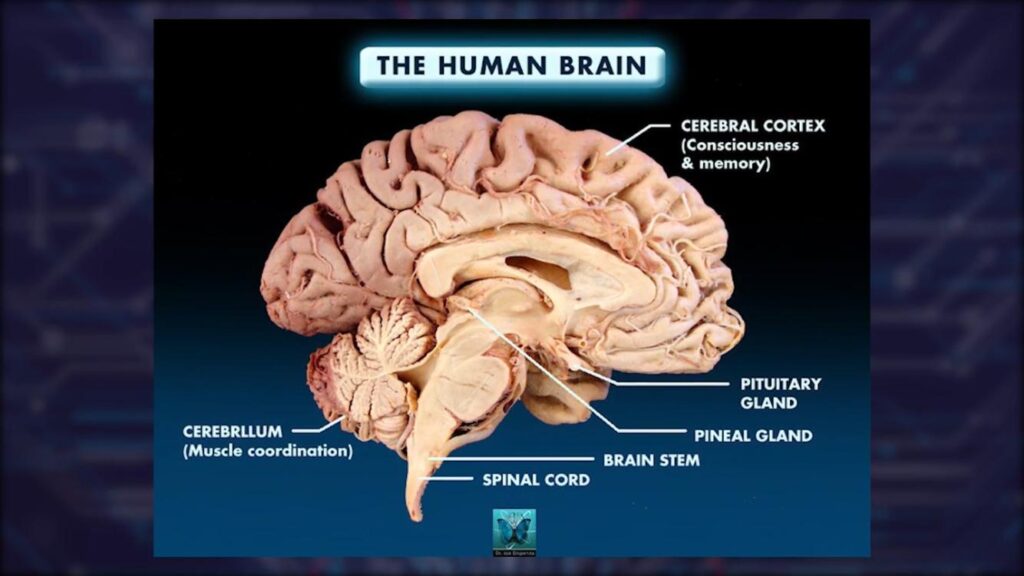

The Brain as an Open System

Microprocessors, no matter how advanced, are constrained by their physical architecture: fixed numbers of transistors, deterministic instruction cycles, and hard boundaries of heat and speed. Their computational scalability is finite — each leap forward demands exponential increases in energy and materials.

By contrast, the brain is biologically plastic. Neurons continuously reconfigure their connectivity, strengthening or weakening synapses in response to experience. This process — neuroplasticity — means that the brain’s “hardware” evolves as it computes. Every thought, every memory, modifies its physical structure. Computation and construction are inseparable.

Infinite Scalability as Adaptive Principle

From an information-theoretic standpoint, the brain’s scalability is functionally infinite:

- It can indefinitely form new representational configurations without a predefined limit on state-space.

- It exhibits recursive learning, where outputs become inputs for subsequent reorganization.

- Its “data model” (the synaptic graph) is self-referential — capable of generating new dimensions of meaning rather than merely adding bits.

This is why comparing the brain to a microprocessor misses the essence. The brain is not a closed circuit executing instructions; it is an open, self-modifying network that grows its own topology.

From Neuron to Innovation

Salk’s work does more than quantify synapses — it bridges biology and computation. The Institute’s Computational Neurobiology Laboratory, led by Sejnowski, has shown that stochastic “noise” in neural firing isn’t error but a computational resource, allowing probabilistic inference far beyond binary logic. This principle now informs neuromorphic engineering, where scientists design chips that mimic the brain’s structure to achieve exponential energy savings and adaptive processing.

Yet even these neuromorphic systems remain bounded by the same limits of material design. Only living neurons possess the capacity to re-scale themselves without end — a property emerging from biochemistry, plasticity, and evolutionary history.

The Takeaway

Where a microprocessor scales by replication — adding more cores, more transistors — the human brain scales by transformation, inventing new modes of connectivity. Its complexity horizon isn’t capped by physics alone but expands through interaction, learning, and meaning-making.

In this light, Salk’s research suggests not simply that the brain is “more powerful” than a computer, but that it belongs to a fundamentally different class of system: one whose scalability is generative, not additive.

The human brain is, in a profound sense, infinite within its own architecture.

(Primary sources: Bartol T.M. et al., “Nanoconnectomic Upper Bound on the Variability of Synaptic Plasticity,” eLife 4:e10778 (2015); Sejnowski T.J., The Deep Learning Revolution, MIT Press (2020); Salk Institute for Biological Studies reports.)